Part 53: Wars in the West

im back bitchesChapter 21 - Wars in the West - 1700 to 1720

It doesn’t take a history lesson to realise that Al Andalus is old, very old. The Jizrunid sheikhs who once ruled over the fishing-village of Cádiz could never have imagined the continent-sprawling sultanate their descendants would one day rule. They could never have imagined the wealth pouring in from lands undiscovered and unconquered, far to the west of the world. They could never have imagined the chaotic wars with the Christian kingdoms in the north, or the catastrophic Fitna that turned brother against brother. It’s been a long tale, but it’s not over yet.

The Andalusia of 1720 would have been foreign to the young, foolish Sultan Utman II, whose reign had heralded the dawn of imperialism. It would have been foreign to the famous Abdul-Hasan, whose life had ended in undignified senility. It would have even been foreign to Grand Vizier Ya'far Hishami, who briefly ruled as dictator in the sultanate's darkest moment thus far.

Once again, however, he winds of change have begun drifting westward. The eighteenth century greets Al Andalus with a new Sultan donning the crown and sceptre, though with powers far more limited than that of his predecessors.

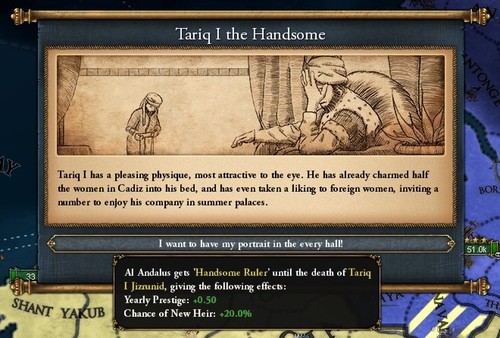

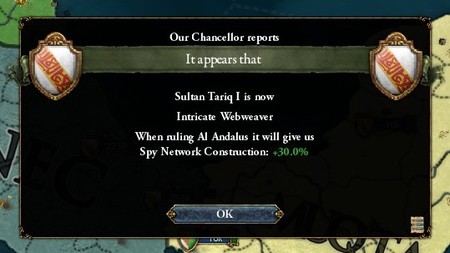

The new Sultan is young, vibrant and exciting. He was widely known for his tall figure and dashing physique, a pleasant surprise when large parts of the Jizrunid family had descended into decadence, with their love of food and women turning them soft and fat.

Even more importantly, Tariq was a strong believer in the constitutional assembly founded by his father, which, after a long line of Sultans determined to assert absolute power, was certainly a breath of fresh air.

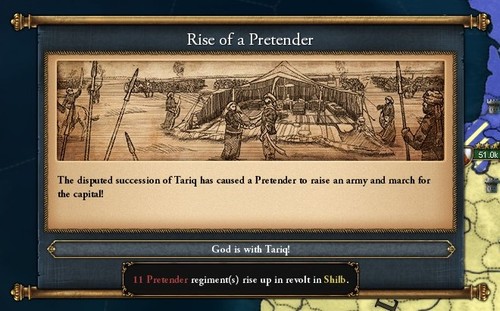

So the 20-year-old was named Sultan in a public ceremony, taking Tariq II as his regnal name in honour of his fallen ancestor and namesake. Thousands of Qadisian peasants flocking to witness the public coronation, desperately hoping he would herald an era of peace and prosperity, while the Majlis quietly dispatched a small force to quash the usual pretender rebels.

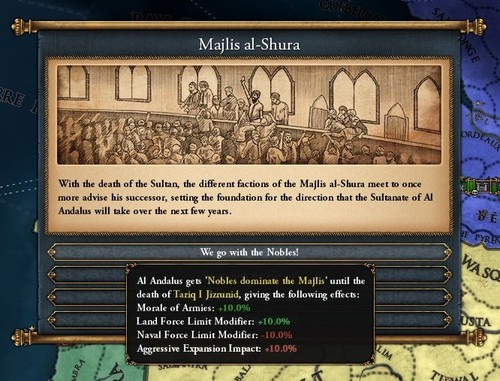

Tariq’s ascent to the throne had other consequences as well, however. It cemented a transfer of power between two fiercely-rivalled branches of the Jizrunid family, and just as ancient titles were torn away from anyone who opposed the Tariqi branch, new honours were bestowed upon those who supported them.

This resulted in a sudden influx of noble families into the Majlis-al-Shura, inflating sultanic support in the constitutional assembly.

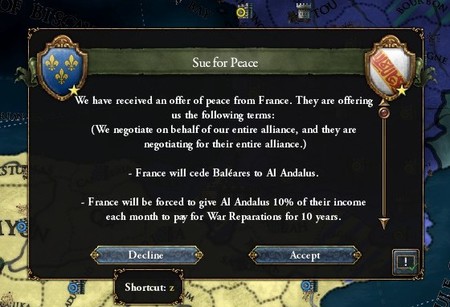

Whilst festivities and revelries were abound in the capital of Qadis, however, there was still a war on in the north. After declaring war on Al Andalus, the war had abruptly turned against the King of France, with most of his neighbours pouncing on the opportunity to curb in the expansionistic monarch.

So it wasn’t much of a surprise when diplomats began turning up in Qadis, desperate for peace. The newly-named noble majority in the Majlis, however, were looking to start their term with a victory, and a big one at that.

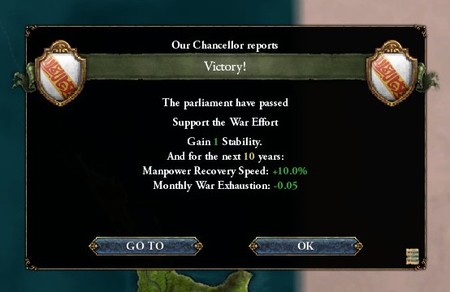

To sustain the war effort, a new act was quickly drawn up and passed through parliament, granting the Sultanate the means and funds to maintain the expensive mercenary army.

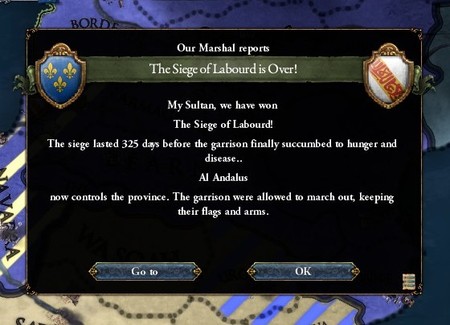

With the full weight of the Sultan and Majlis backing them, the reinvigorated Andalusi army drove northward and across the Pyrenees once more, laying siege to the fortress of Labourd for the umpteenth time.

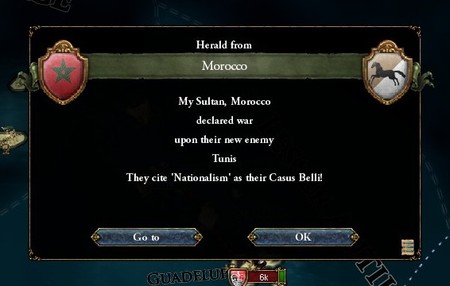

In the south, meanwhile, Andalusi diplomats in Marrakesh reported that the Almoravid sultan had declared a war of his own, against none other than the Emirate of Tunis - a historic Jizrunid ally and important player in the regional balance of power.

Going toe-to-toe with the Kingdom of France demanded the full attention of Qadis, however, and the Majlis could do nothing but watch as the banners were raised and guns were loaded, with thousands of Moroccan soldiers flooding into Tunis before the end of the year.

The siege of Labourd dragged on for almost a year as the Andalusi were forced to starve out the garrison, with disease breaking out amongst the besieging force more than once. Fortunately no relief forces arrived, and the defenders eventually caved in and surrendered.

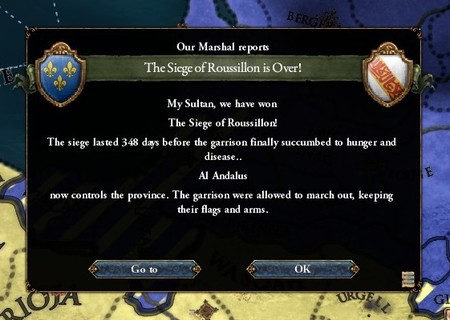

With the west under their control, the Andalusi marched eastward and began preparing to besiege Roussillon, hoping to completely encircle the Pyrenees before the French could interfere.

Once again, however, the siege was dragged out for twelve long months, but it capitulated without the sight of blue banners. The golden banners of the Jizrunid dynasty was hoisted above the parapets of Roussillon just as the winter of 1702 began to set in, and with that, the French were forced to the negotiating table.

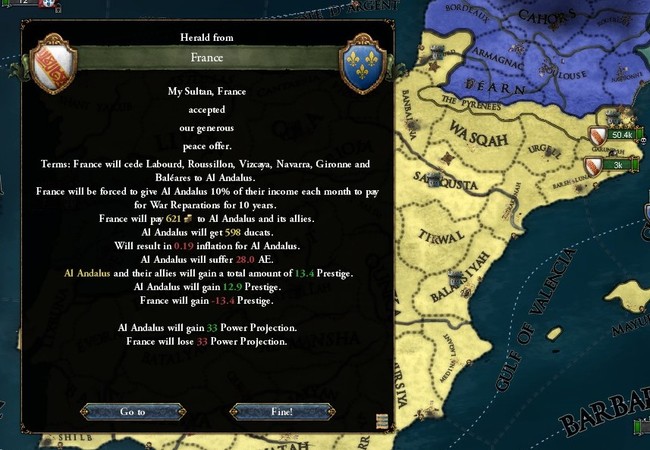

Holding all the cards, Andalusi diplomats dictated the negotiations over the next few weeks, and the French King was forced to cede almost all the territories he’d captured in previous wars. And with that, in a single stroke of black ink, everything the French had achieved in the past half-century was undone.

The young Sultan Tariq didn’t involve himself much in the actual negotiations, but he wasn’t wasting his time, not at all. Even before the peace treaty had been announced, Tariq delivered a speech to the Majlis-al-Shura, hoping to rouse support for yet another war.

It was a close-cut thing, but with the Celts still steadfast allies of the Portuguese, the Majlis decided to postpone the reconquest. It would have to come sooner or later, however, and with so many young nobles now making up the assembly, the former was looking increasingly likely.

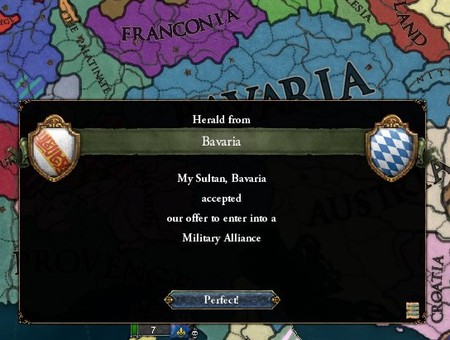

The older, wiser members of the Majlis were also busy. Determined to avoid any more defeats to the French, who would almost certainly be back before too long, the Andalusi managed to strike an alliance with the Electorate of Bavaria. Not the power it once was, perhaps, but a good eastern counterweight to French aggression.

A defensive treaty was also drawn up binding Al Andalus to the Archbishopric of Liege, which now ruled over large parts of the Low Countries, one of the richest and most densely-populated regions in Europe.

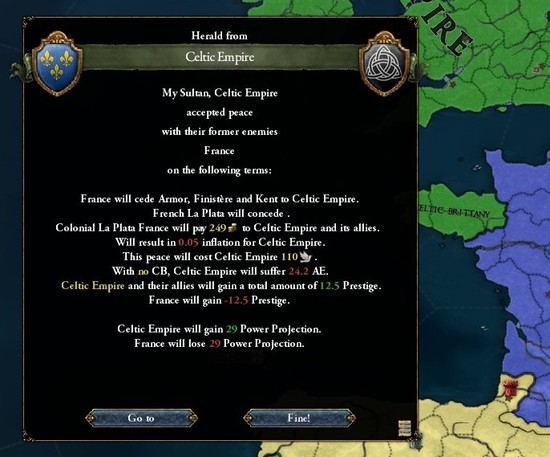

Whilst the Andalusi were busy reforging alliances, the war between the Celtic Empire and France came to an end, with the High King demanding nothing less than Brittany, once a kingdom within the Celtic Empire.

In the vast western continent of Gharbia, meanwhile, the Hishami dynasty (which now ruled over the colony of Ibriz autonomously) was having trouble suppressing a wave of native rebellions.

The Hishami had wanted autonomy, however, and the Majlis was going to give them exactly that. Not a single Andalusi soldier would be sent there, not until the self-proclaimed Emir was on his knees and begging for help.

Instead, the assembly cast their nets further afield, looking to the endless islands at the far reaches of the Pacific Ocean.

The Berbers had already claimed a vast continent in the south, one said to be at least as large as Gharbia, and thrice as rich. The Majlis had no interest in creating another unruly colony, however, instead settling for a few islands dotting the waters around it.

In what was becoming something of a routine, prisoners and volunteers alike were sent to settle these islands, asserting Andalusi claims in the region. And before too long these settlements grew into small towns and villages, though not without attracting the unwanted attention of the Celts.

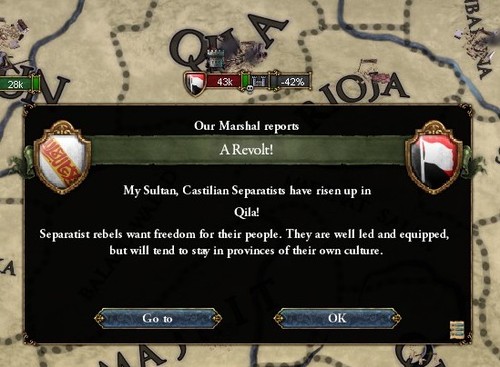

Back in Iberia, a large Castilian revolt broke out in Qila, led by a local prince who was protesting his lack of representation in the Majlis (especially since both the Aragonese and Leonese had seats of their own in the assembly).

The Andalusi army, which had had little to do since the end of the French War, were quickly whisked to the scene. The largely-untrained army of peasants, butchers and shopkeepers was crushed without much ado, though Sultan Tariq specifically commanded his forces to abstain from sacking Qila. The city was already a shadow of its former self, and the Castilians would have to be brought back into the fold, eventually.

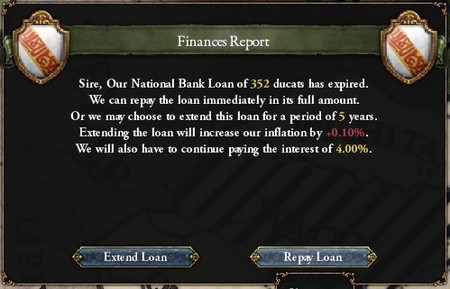

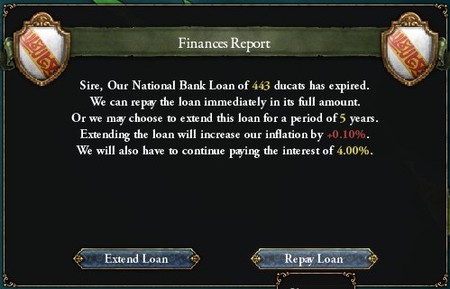

The lack of war did have the advantage of increasing revenues though, with most of the money quickly channeled into repaying long-running loans and debts.

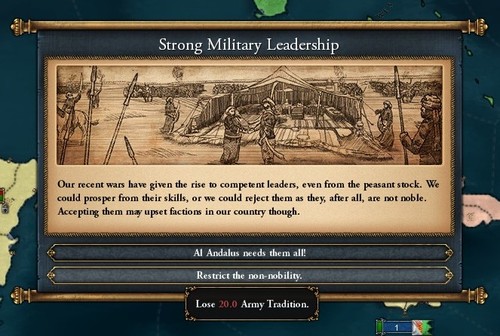

War was on the horizon, however, that much was certain. Sultan Tariq was desperate to reconquer Portugal, seeing the small kingdom as a blight on his father’s legacy. Towards that end, he began making moves to massively expand the size of the Andalusi army, both through conscripts and mercenaries.

All of this came with a price, however. In return for passing Tariq’s expansion acts, the Majlis demanded a decree that limited the officer pool to men of noble birth or high station. Faced with little choice, the Sultan agreed, sacrificing the untapped imagination of the masses for more guns and more men.

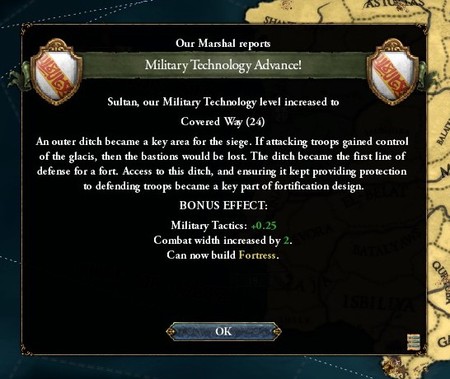

The Majlis did recognise the need to modernise their fortresses, however, especially those on the French border. The Andalusi would never be able to match the French in pure numbers, but they did have the Pyrenees, so significant investment was put into digging trenches and training garrisons around the fortresses that dotted the massive mountain range.

With that all said and done, Al Andalus was well on the road to recovery by the end of the decade. Sultan Tariq was quickly proving himself a capable leader, already pulling the strings in the parliament despite his relative inexperience in politics.

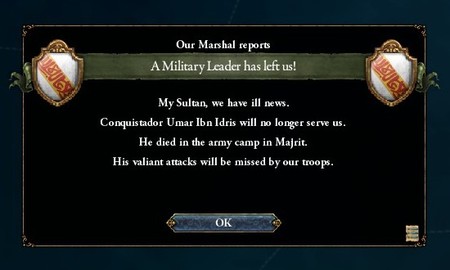

Bad news arrived shortly afterwards, however, with the death of Umar ibn Idris - Supreme Commander of all Andalusi armies. The old general had been one of the brightest Andalusi generals in decades, with a career stretching from the earliest days of the Fitna to the very last French war, earning himself a reputation for creativeness on the battlefield and devotion to the Tariqi Jizrunids off of it.

Sultan Tariq immediately ordered the construction of a massive mosque in the capital, named Masjid al-Idrisi in honour of the famous commander. Following suite, similar mosques were constructed in Qurtuba and Tulaytullah, consisting of huge, arching complexes that stretched across a dozen acres and cost thousands of dinars.

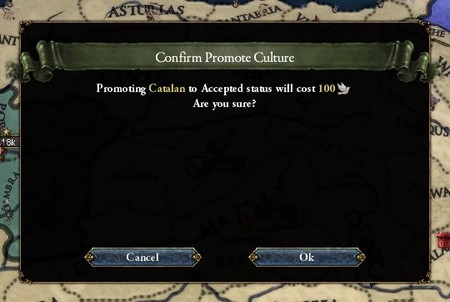

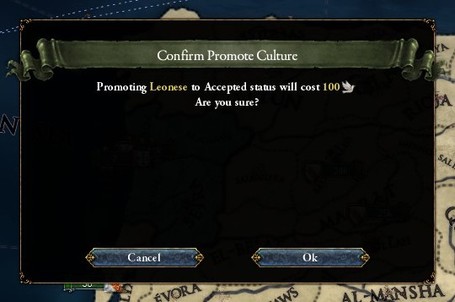

Back in the noisy, smoke-filled assembly of the Majlis-al-Shura, meanwhile, the League of Merchants managed to pass an act that awarded the Catalan and Leónese minorities full-fledged rights. As non-Andalusi Muslims, they were still second-class citizens, but they now had parity with both the Aragonese and the Castilians.

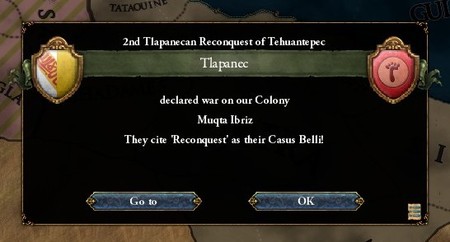

In the west, meanwhile, the Hishami rulers of Ibriz had managed to defeat the native Mayan insurgents, but it left them with a weakened army barely capable of holding the peace, thus encouraging the Tlapanec Emperor to yet again declare war on the Andalusi colony.

This was a step too far, of course, and the Majlis quickly authorised the transport of more than 50,000 soldiers across the Atlantic. The army was led by the newly-appointed Supreme Commander Mundir Aliyah, a minor nobleman who’d served with distinction in the recent French war.

This would be a short war, everyone was convinced they’d be home by Eid.

And they were. The natives were technologically and numerically inferior, and the Andalusi plowed across Central Gharbia within half-a-year, besieging and razing Tlapan City as they did so.

Despite a brutal sacking of their capital the Tlapanec army put up resistance, refusing to surrender without meeting on the field. Their eagerness to fight made it easy to bait them into a battlefield of Andalusi choosing, however, and so a 50,000-strong native force met with the Muslims on the fields of Cuetlaxtlan.

The battle began on a humid morning in the summer of 1714, and 20,000 natives littered the field before nightfall.

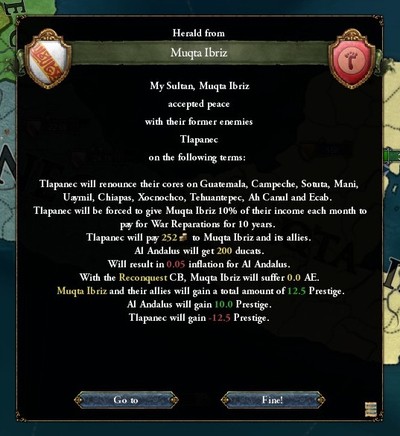

Needless to say, the humiliating Tlapanec surrender was fast becoming something of a tradition. The natives were punished harshly, forced to cede large tracts of fertile Nahua land to the Muqta of Ibriz, directly administered by the Hishami Emirs.

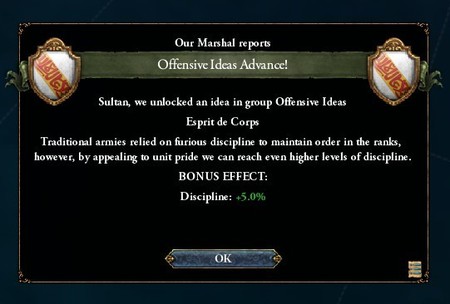

Beyond mere land grabs, Sultan Tariq actually had a vested interest in the war, as it was the first test for his newly-reconstructed army. They had performed well enough, though it wasn’t long before the Sultan began signing off new policies, looking to tighten up the discipline and professionalism of his forces.

What the Sultan was less interested in, unfortunately, was the navy. Still, the League of Merchants had managed to strengthen the Andalusi Fleet over the past few years, despite recent defeats on the seas.

And thus, by 1717, the fleet rolled out with no less than 17 top-of-the-line twodeckers, massive warships that had hundreds of guns lined up along two huge decks.

And they spared no expense on the traditional flagship, constructing a first-rate ship-of-the-line dubbed Tariq, for obvious reasons.

In Christian Europe, the young kingdom of Provence declared war on France. A bold move, but one that might just pay off, with the French still reeling from the previous bout between the two neighbours.

The first year of the war went firmly in favour of the Occitan principality, following a series of victories in the south of France. The Provencal armies certainly impressed, at least as well-drilled as the Andalusi forces were, and it seemed like the balance of continental power was beginning to shift once more.

With the French engaged in another war, the Majlis turned westward, where the Iberian cyst was waiting to be popped. The Celtic Empire would still defend the vulnerable kingdom of Portugal, but the Sultan wasn’t willing to wait for fate to turn against the Celts, and the assembly was determined to reconquer the rich city of Porto.

Sultan Tariq was only too pleased to authorise the long-awaited act of parliament, and so the Sultanate of Al Andalus declared war.

The Portuguese army was massively inferior to the Andalusi, so they fled south within hours of the war breaking out, led by none other than their king. The Andalusi thus marched on Porto without opposition, with the city surrendering mere weeks later.

Once the north was under their firm control, the Andalusi marched southward, pinning down the Portuguese force just outside Beira, where the Christians had decided to make their last stand.

Facing the numerically-superior and better-trained forces of Sultan Tariq, the Portuguese stood little chance of somehow coming out on top. The battle ended in a crushing defeat for the Christians, with thousands gunned down and ridden into the ground, and thousands more chained and scaffolded.

The newly-rebuilt Andalusi Fleet also faced its first test, handily defeating the Portuguese navy in a short battle in the Lusitanian Sea.

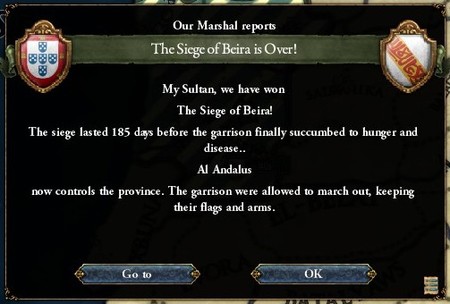

This was followed by the fall of Beira to the Andalusi, with the badly-fortified city holding out for a good few months before succumbing.

With Portugal fully-occupied and Iberian waters firmly-controlled by the Andalusi, the Majlis decided to send a 30,000-strong expeditionary force to seize victory in Gharbia, where the Celts had decided to strike.

And the first battle between Andalusi and Irishman ended in victory for the former, with the Celts forced to retreat after suffering massive losses in men and artillery.

Whilst the Andalusi army focused on establishing their authority in Central Gharbia, the Celts had quickly spread out and captured large parts of the north, which stood helpless before the green onslaught.

Back in the east, the Andalusi Fleet were met head-first by the Celtic Navy in the Straits of Gibraltar. The Andalusi had a huge advantage in numbers, especially in the heavy warship department, but that proved to be of no avail…

In what was surely one of the biggest blows to the Andalusi naval effort, Celtic ingenuity and tactics in the tight confines of the Straits left them as uncontested victors in the ensuing battle, sinking every single Andalusi twodecker whilst losing just one of their own.

There could be no doubt about it now, the Celts would have mastery over the seas.

This was not good news, obviously, as it now left the Andalusi army stranded in Gharbia without any hope of reinforcements.

Still, there was nothing to do but push onwards and forwards. Supreme Commander Mundir Aliyah still had command over Andalusi forces in the west, ordering a march on Celtic positions further north. The islanders could well have mastery over the sea, but that didn’t count for anything if they lost their colonial holdings.

The Andalusi recaptured large parts of northern Gharbia over the next few months, driving the numerically-inferior Celtic army eastwards as they did so. Once a few irregular Hishami regiments arrived to reinforce the Andalusi, Aliyah finally felt confident enough to meet the Celts, with battle breaking out in the early months of 1719.

Fortunately for the Andalusi, the Celts displayed none of their naval brilliance when fighting in the muddy banks of the Mississippi, forced to retreat after suffering thousands of losses in just three hours of battle.

Of course, this was exactly when they landed another large army in Ibriz, numbering some 40,000 well-armed and well-drilled men.

Not to mention another 60,000 reinforcements to back them up, this time disembarking at Andalusia’s holdings in Juzur Qarbiya. How those blasted isles had so many men of fighting age, no one could imagine.

Supreme Commander Aliyah rushed south with all the haste he could muster, desperate to halt the Celtic advance before they overran half the continent. Forced to make a dangerous crossing across the Mexican Gulf, he managed to reach them just as the walls of Petén were being blown apart, and despite marching them half to death, he threw his entire force at the Celtic army.

It was risky, no doubt, a gamble. But if the Andalusi couldn’t maintain their dominance on land, then they had no hope of emerging from the war victorious.

And despite having slightly inferior numbers, they did just that.

More, even, the Andalusi managed to pull off a massive victory. 20,000 fallen and captured Celts, for just 5000 Andalusi. The numbers were staggering, and a good deal of the credit was rightfully awarded to the young commander Aliyah, who used a combination of rapid battlefield movements and combined assaults to utterly annihilate the enemy formation.

The battle would certainly leave the Celts reeling, but it didn’t necessarily herald the end of the war. The Majlis would be forced to meet a few days later, with their gains on land surely outweighed by their naval losses, to decide whether or not they should sue for peace.

Beyond this war, however, the world at a large was beginning to change. It had been sparked off by the failed independence revolutions in Gharbia and separatist uprisings in Europe, and though they might have seemed like minor rebellions at the time, half the world would be burning in the name of revolution before too long.

Which of the old regimes would still be standing by the end of the century?

World map added: